The China Signal - April 16

Sinovac scores with Copa America, BYD's Brazilian SkyRail, China's commercial presence the key to early "mask diplomacy"

G’day, and welcome to The China Signal! This week, a milestone in BYD’s “SkyRail” project in Brazil; the Copa America football tournament is boosted by some deft vaccine diplomacy; an analysis of China’s “mask diplomacy” that highlights the power of China’s growing commercial presence in the region; a discourse analysis of Beijing’s Spanish language state media; plus more. Read on.

Also, a big welcome to a whole swathe of new readers to The China Signal this edition. Thank you to TCS reader Bethany Allen-Ebrahimian of Axios for the mention this week. Her own weekly newsletter on broader China themes is well worth a read.

Deals and Financings

Brazil 🇧🇷

On April 8th, BYD ushered in a new milestone, as its Bahia SkyRail vehicle rolled off the production line in Shenzhen. The Bahia SkyRail, located in the city of Salvador, Bahia State, Brazil, is the world’s first SkyRail line to be partially built above the sea.

The Bahia SkyRail Line has 25 stations covering a total length of 23.3km. It will be connected with Bahia’s existing subway to form a comprehensive public transportation network.

It’s not clear when the project is due for completion. It is partly financed by the Inter-American Development Bank with a 20 year, $240 million loan towards capex. Total construction cost is expected to be approximately $840 million.

Reading this press release, one can’t help but notice the meshing of corporate and state objectives, right down to the “suggested tweet”:

Vaccine Diplomacy

Brazil 🇧🇷

As I mentioned in TCS April 2:

Also, China’s domestic vaccination campaign is clearly accelerating. As I noted in TCS March 19, I believe China’s domestic production and distribution capacity is a potential restraint to Beijing’s ability to fulfil vaccine commitments abroad. The accelerating campaign in China suggests that either Beijing is prioritising domestic inoculations over their foreign diplomatic efforts, or that their productive capacity has increased to fulfil both domestic and foreign commitments. With Beijing’s approval of another local vaccine “ZF2001” in mid-March, we could be looking at the latter scenario.

Brazil’s Butantan lab suspended production last week as they wait for further supply of Sinovac’s active ingredient from China. Is this an indication of China approaching its current productive constraints? I’m not sure, but it’s something worth monitoring for more information.

Brazil’s virus outlook darkens amid vaccine supply snags - The Washington Post - April 11, 2021

Stalled supplies of the AstraZeneca vaccine in January amid pressure for Brazil to begin its vaccination campaign prompted the Health Ministry to acquire tens of millions of shots from Sao Paulo state’s Butantan Institute, which is mixing an active ingredient from China with a sterile solution and bottling it. The shots were the fruit of the state’s negotiations with Chinese company Sinovac and went ahead despite Bolsonaro’s criticisms.

Both Brazilian labs face supply problems. Butantan said Wednesday it was suspending production while it awaits shipments of the active ingredient from China.

China 🇨🇳

China’s locally developed COVID-19 vaccine candidate that uses messenger RNA (mRNA) technology could start late-stage clinical trial overseas as early as next month, official media said on Tuesday.

ARCoV, the China-developed mRNA vaccine candidate that is furthest along the clinical trial process, may get overseas approval to conduct Phase III clinical trial by as early as end-April, China National Radio said in an article on its website.

China has approved four locally developed coronavirus vaccines for general public use and a fifth for smaller-scale emergency use but none of them uses the mRNA platform.

Overseas clinical trials could formally begin in May, and South America could be a “first option” as a trial location, the report said, citing an interview with Ying Bo, founder of Suzhou Abogen Biosciences.

I’ll keep an eye on which countries in Latin America secure these trials.

Paraguay 🇵🇾

TCS reader and New York Times Brazil bureau chief Ernesto Londoño gives an excellent recap of the growing domestic political pressure in Paraguay to approach Beijing for vaccines, possibly at the price of their diplomatic relationship with Taiwan.

Colombia 🇨🇴 + Argentina 🇦🇷 + ⚽️

If public diplomacy is all about winning hearts and minds, why not align yourself with football, the continent’s obsession?

Chinese company donates 50k COVID vaccines to CONMEBOL ahead of Copa America - April 13, 2021

[Sinovac] will donate 50,000 doses of their COVID-19 vaccine for national teams to use ahead of the Copa America, CONMEBOL announced on Tuesday.

The vaccines will also be used for other CONMEBOL competitions.

This year’s tournament is co-hosted by Colombia and Argentina, kicking off on June 13, and concluding on July 10.

Uruguay’s Secretary of Sport Sebastián Bauzá has claimed credit for facilitating CONMEBOL’S partnership with Sinovac:

~Paraphrased Translation~

As the Secretary of Sport explained, a connection between CONMEBOL, China’s ambassador in Uruguay and Sinovac representatives was made following an informal meeting between Uruguay’s President Luis Lacalle, CONMEBOL head Alejandro Domínguez and himself. After Dominguez expressed concern about not being able to play the Copa América and all the CONMEBOL tournaments due to a lack of vaccines, President Lacalle offered to make contact with Sinovac.

Así lo explicó el secretario nacional de Deporte: «En ese encuentro informal, Domínguez le trasladó el problema de no poder jugar la Copa América y todos los torneos de la CONMEBOL, que no tenían vacunas y el presidente dijo que él podía hacer un contacto con Sinovac. Y así fue».

Even Lionel Messi had a hand (a foot? Sorry for the the terrible pun) in sealing the deal:

The deal with the Chinese pharmaceutical firm Sinovac was secured after Messi donated three autographed sweatshirts. “Sinovac’s directors manifested their admiration for Lionel Messi, who kindly sent us three shirts for them,” tweeted the Conmebol official Gonzalo Belloso.

This example segues nicely into the following section, highlighting how we should be careful to always assume China’s vaccine diplomacy only emanates from Beijing as a top-down directive, as part of a broader “grand plan”. As the below report accounts, often it is a mix of pragmatism and opportunism, where domestic political motives in Latin America are just as significant as Beijing’s. The key point is that there is an ongoing need for vaccines, that the region’s political leaders are facing a lot of pressure to secure supply for their citizens, and that in Latin America, Beijing remains the most willing and agile provider.

Mask Diplomacy

Chile 🇨🇱

A report by Francisco Urdinez.

Many observers argue that China has a one-size-fits-all approach to diplomacy: settling on a singular model and then exporting it, largely at the direction of the central government. This is certainly the expectation that many analysts have held for China’s mask diplomacy, a high-profile diplomatic initiative closely tied to Beijing’s reputation. In practice, however, that has not been the case.

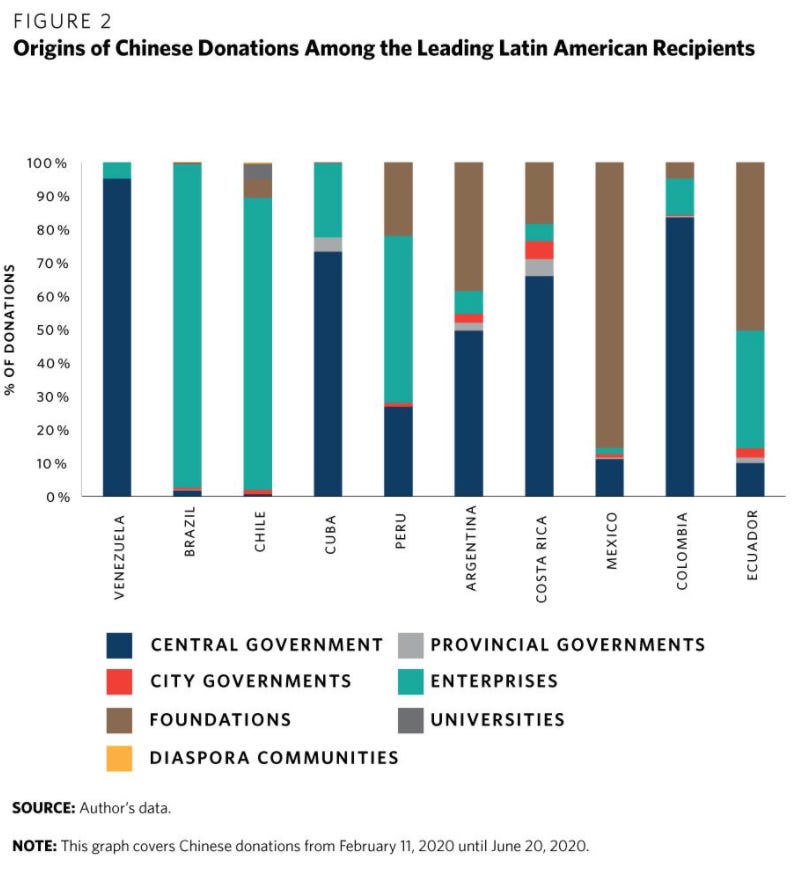

In fact, Chinese donations during the pandemic to countries in Latin America and the Caribbean in general—and to Chile in particular—have not been centralized around a single actor or program. Instead, these donations from China have been channeled through multiple parallel tracks. Ultimately, mask diplomacy is best thought of as a hodgepodge of actions by a diverse cast of Chinese donors rather than the centralized outgrowth of a unitary national policy. In Chile, at least, Chinese actors have displayed considerable improvisation in carrying out this mask diplomacy.

In the early months of the pandemic, however, Chile was among the top recipients of Chinese donations to Latin America and the Caribbean. Between February to June 2020, Chile received medical supplies worth $9.5 million in donations from various Chinese companies, foundations, and provinces as well as the Chinese central government. This made Chile the third-largest recipient of Chinese medical assistance in Latin America, behind only Brazil ($23 million) and Venezuela ($43 million).

Be mindful that the above graph only shows proportions - the actual amount of Chinese donations varied considerably between countries.

Instead of a story of two governments making big bilateral deals, China’s mask diplomacy in Chile showcases how prior connections forged by local actors can be repurposed and can evolve. … This analysis of China’s mask diplomacy in Chile is particularly relevant since it shows how improvisation and adaptation plays a key role in China’s current foreign policy in terms of translating policy guidelines with a global reach into practice.

Argentina 🇦🇷

In TCS February 19 I noted China’s donations of military hospitals to Argentina’s armed forces. The U.S. Southern Command (“SOUTHCOM”), which covers the United States’ military operations and relations with Latin America and the Caribbean has followed suit, donating three military hospitals of their own in a recent visit from SOUTHCOM Commander Admiral Craig Fuller.

With Argentina visit, US military flexes 'soft power' in competition with China - April 8, 2021

On Twitter, Southern Command reported that it donated three military field hospitals to help Argentina treat Covid-19 patients. The donation was funded by Southern Command's Humanitarian Assistance Program.

Additionally, Southern Command noted that it has worked "closely" with Argentina during the pandemic, including donations of protective equipment, medical supplies, monitoring and screening tools.

Public Diplomacy

Broader Latin America 🏔🏝

Chinese-style democracy - Global Americans - April 14, 2021

Some interesting analysis by TCS reader Juan Pablo Cardenal, part of research that will be published in July.

The preliminary findings of a study of disinformation and propaganda in the Spanish-language outlets of Chinese state media, currently being undertaken by Global Americans and CADAL, shed light on how China takes advantage of the development of its COVID-19 vaccine and its perceived economic success. These advances fuel the narrative of China as an emergent scientific and technological power and present China’s autocratic system as a suitable development model for the developing world. The analysis of content and terminology of a representative selection of articles reveals Beijing’s efforts to disseminate a recognizable and seductive narrative adapted to Latin American audiences.

For instance, mentions of Chinese vaccines are often accompanied by positive wording, associating them with words such as “efficacy,” “safety,” “contribution,” “responsibility,” “leadership,” or “public good.” In contrast, Western vaccines are linked to negative terms such as “death,” “disease,” “problem,” “adverse reaction,” “side effects,” “hoarding,” “nationalism,” or “delay,” leading to suspicions about their efficacy and safety. However, these associations serve yet another purpose: enabling Chinese state-media outlets to deploy an ideological discourse to mislead the developing world.

This is a discourse wrapped in a perfectly calculated and diplomatically charged rhetoric of cooperation. Terms like “friendship,” “aid,” “generosity,” “multilateralism,” “donation,” “responsibility,” and “commitment”; and government slogans like “health community,” “a shared future for humanity,” and “mutual respect” are also part of the official narrative. This way, the Chinese regime poses as a faithful ally for Latin America and as leader of the developing world in the face of Western hegemony. It presents the supposed superiority of its model, which Xi Jinping believes “opens a new path for the modernization of other developing countries,” to address current and future challenges.

“Vaccine diplomacy, China’s strategy to retake ground in the region”

~Paraphrased translation~

Federico Urdinez, an expert on China at the Catholic University of Chile, asked in a study in seven Latin American countries about their perception of China. The response of the interviewees was the same: coronavirus. The Wuhan market was still fresh in the memory of Latin Americans, who pointed to them as the culprits of the misfortunes they still suffer.

At first, "mask diplomacy", those Chinese donations received in the worst months of the pandemic, did not work, concludes Urdinez. But when the Catholic University of Chile repeated the study months later (which is still in process), opinions changed. “With the arrival of vaccines, they reversed the reputational damage that they couldn’t reverse with masks. China’s image has now improved among Latin Americans ”, explains Urdinez.

Federico Urdinez, experto en China de la Universidad Católica de Chile, preguntó en un estudio en siete países latinoamericanos por su percepción sobre China. La respuesta de los entrevistados se repetía: coronavirus. El mercado de Wuhan todavía estaba en la memoria de los latinoamericanos, que los señalaban como los culpables de las desgracias que todavía sufren.

En un principio, la “diplomacia de las mascarillas”, esas donaciones chinas que llegaban en los peores meses de la pandemia, no dio resultado, concluye Urdinez. Pero cuando la Universidad Católica de Chile repitió meses después el estudio - todavía en proceso- las opiniones cambiaron. “El daño reputacional que no habían logrado revertir con las mascarillas, sí lo hicieron con las vacunas. Ahora sí se percibe una mejoría en la imagen pública de China entre los latinoamericanos”, explica Urdinez.

Argentina 🇦🇷

“Confucius Institute connects hundreds of Argentinians with Chinese culture”

*Xinhua is a state-sponsored media outlet.

I wrote about the opening of this particular Confucius Institute in October.

~Paraphrased translation~

Five months after its official inauguration, the Confucius Institute of the National University of Córdoba (UNC) in Argentina has brought together 700 students from all over the South American country in a new “summer camp” experience, which consists of virtually visiting various provinces of China for eight days.

Currently, the Institute seeks to expand within the province of Córdoba to reach the Popular Universities. These are are teaching spaces attached to the UNC Extension Secretariat, located in the most remote areas of this district.

According to the UNC’s Dean of the Faculty of Letters Elena del Carmen Pérez, there are already more than 120 Popular Universities in the province of Cordoba where Chinese-Mandarin is being taught.

BUENOS AIRES, 9 abr (Xinhua) -- Tras cinco meses de su inauguración oficial, el Instituto Confucio de la Universidad Nacional de Córdoba (UNC), en Argentina, ha logrado reunir a unos 700 estudiantes de todo el país sudamericano en una nueva experiencia llamada "Summer Camp" (campamento de verano), que consiste en visitar de manera virtual diversas provincias de China durante ocho días.

Actualmente, el Instituto busca expandirse dentro de la provincia de Córdoba buscando llegar a las Universidades Populares, que son espacios de enseñanza adscritos a la Secretaría de Extensión de la UNC, ubicados en las zonas más remotas de este distrito, donde a menudo prevalecen dificultades para que los jóvenes se trasladen a los grandes centros educativos.

De acuerdo con Pérez, ya existen más de 120 Universidades Populares en la provincia cordobesa donde se busca que sea impartido el chino-mandarín.

Trade

Panama 🇵🇦

TCS reader Evan Ellis’ latest in his series of China-LatAm bilateral reviews:

China’s advance in Panama: An update - The Global Americans - April 14, 2021

This piece examines the evolution of China’s position in Panama under the Cortizo government. It finds that China’s advance has suffered significant, if not necessarily enduring, setbacks under Cortizo, reflecting a combination of enhanced legal scrutiny, problems inherent to the Chinese projects themselves, and the adverse effects of the pandemic and corruption on the commercial and administrative environment in the country.